In Freestyle, our latest exhibition, ���������� has commissioned the emerging practice Space Popular to illustrate how the evolution of mass media and pop culture has influenced the development of architectural styles over more than 500 years. Through a site-specific installation, immersive virtual reality, and objects from the world-class ���������� Collections, the exhibition teases out the links between the printing press and the Renaissance; the camera and revivalism; the movie theatre and Modernism; the TV set and Postmodernism; the internet and late Modernism; the VR headset and architecture’s future.

In the exhibition’s section on the revivalism of the 19th century, you’ll find an 1860s photograph showing the Egypt section of the Fine Art Courts at the Crystal Palace. The Courts aimed to demonstrate the historic art of (then) Persia, Greece, Egypt, Turkey, Spain, Portugal, Madeira, Italy, and France. The image shows how the rise of photography made it possible to share visual experiences around the world in unprecedented ways, contributing to ‘Egyptomania’ as interest in ancient civilisations soared.

But how was this reflected in architectural education? Were students instructed to embrace, or reject, the styles of their predecessors?

Around the same time the photograph was taken, Matthew Digby Wyatt, one of the creators of the Fine Arts Courts, addressed architecture students in a lecture at ����������. More archival material from the ���������� Collections helps illuminate how architectural styles were disseminated through teaching.

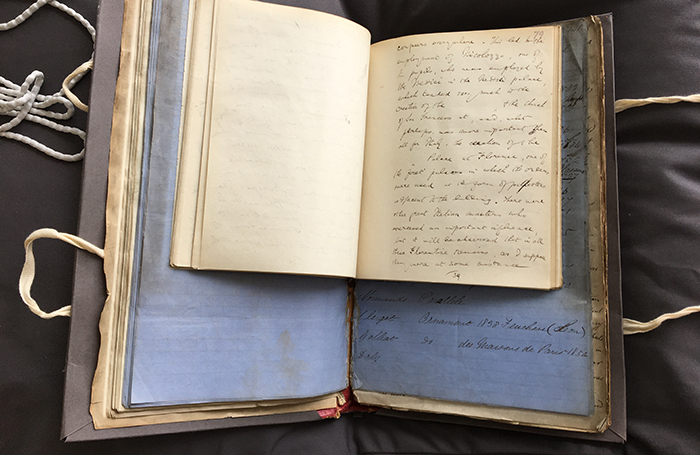

Exams in architecture were a relatively new occurrence when Wyatt took to the lectern in March 1865. ���������� “Voluntary Examinations” had been introduced in 1862, and Wyatt’s task that day was to deliver a lecture on architectural styles from the 16th to the present century, as part of a series on the history and literature of architecture that aimed to prepare students for these exams and give them a grounding in the history of style. Notes from all these lectures were painstakingly transcribed, and can be found bound together in a mighty volume that was presented to the ���������� Collections in 1878. They offer a unique glimpse into the training of a 19th century architect, who was expected to know their classical literature and renaissance architects; their Boccaccio from their Bramante.

Style was at the centre of Wyatt’s lecture. He told his students they should read the literature of, and study buildings by, the “masters” of both gothic and Italian renaissance buildings in order to arrive at a “wholesome eclecticism” that drew from historic styles without directly imitating them. Exhibits like the Crystal Palace, as well as the British Museum and the V&A (then the South Kensington Museum) would enable them to draw on the widest possible range of stylistic sources, as the exchange of visual culture expanded around the world. The result was an explosion of simultaneous revivalist styles, as uncovered in the exhibition.

“If you… in the future should look back and ask, ‘what was the style of this period?’ the reply would be that we had no style at all”

Matthew Digby Wyatt, 1865

Today’s architecture students can recreate the 19th century educational experience by consulting the classics Wyatt recommended in our rare books collection – covering early and rare editions from the likes of Serlio, Alberti, Palladio and Piranesi. Or visit the exhibition, where Space Popular animate the sources that architects have turned to for instruction and inspiration over generations through virtual reality and an installation creating a dialogue with the ���������� Collections.