To celebrate , we've delved into the ���������� Collections to explore alternative proposals for London buildings through history.

You can discover more about these schemes and plenty more through the ����������pix image library, our online resource of more than 95,000 drawings and photographs from the ���������� Collections.

Join the conversation with and .

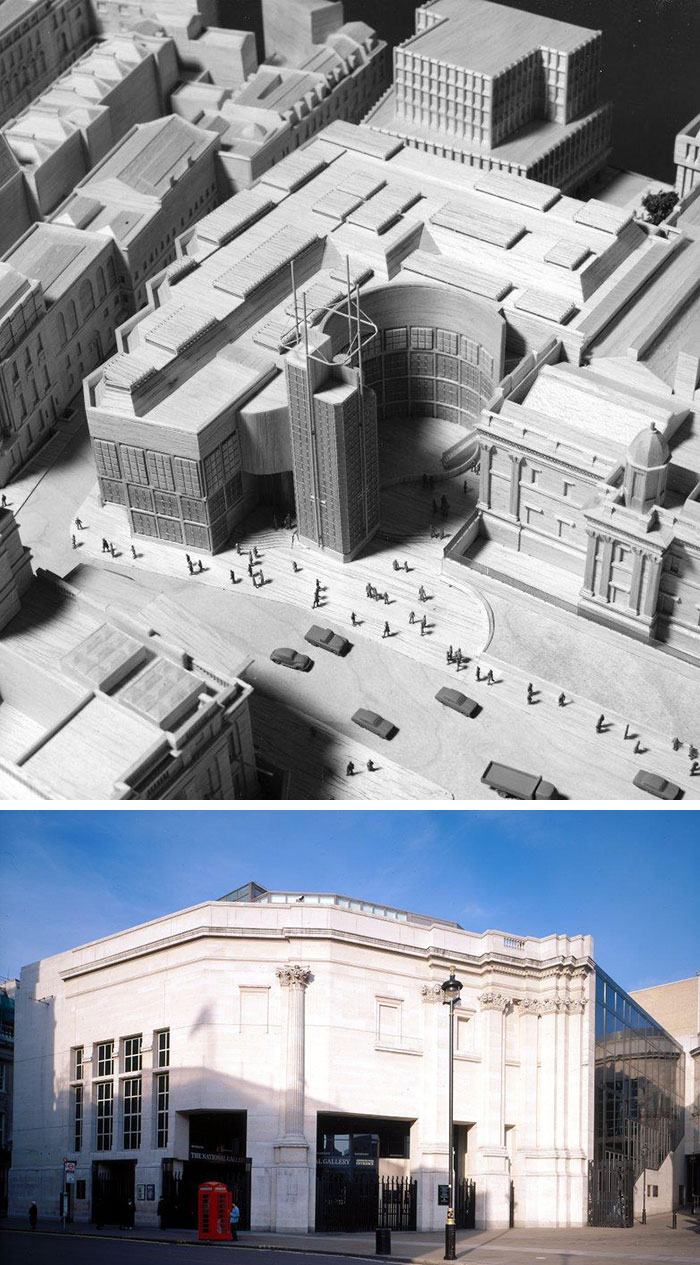

1983 model for the National Gallery Extension by Ahrends Burton & Koralek

Perhaps one of the most memorable architectural debates in recent history centered around the design for the National Gallery's extension, opened as the Sainsbury Wing in 1991 and completed to designs by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. A 1982 design competition prompted proposals from high-profile architects including Richard Rogers and R. Seifert & Partners - but the winning entry was this High-Tech scheme by Ahrends Burton Koralek. This design became a battle-ground for debate between architectural neo-modernists and traditionalists, among them Prince Charles, who slammed the proposal in a speech at the ����������. Ahrends Burton Koralek's scheme was denied planning permission in 1984, and replaced with the Venturi Scott Brown & Associates design that now defines the north-west corner of Trafalgar Square.

Top: 1983 model for the National Gallery Extension by Ahrends Burton & Koralek, courtesy ���������� Collections, and below: The Sainsbury Wing photographed in 1998, as built to the designs of Venturi Scott Brown & Associates, courtesy Janet Hall / ���������� Collections

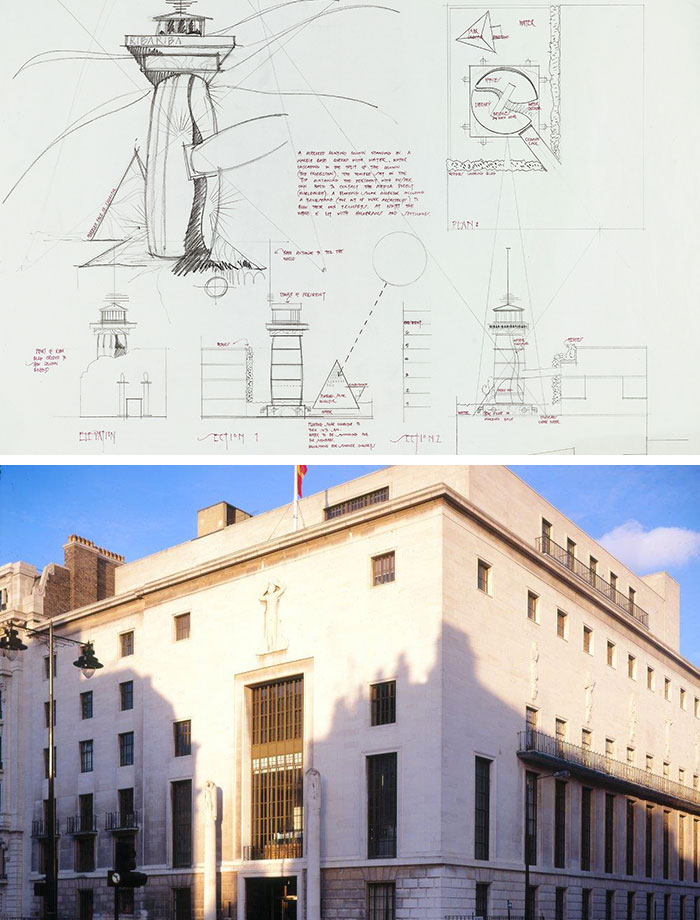

1981 competition sketch for additional office and library space for the ����������

This tongue-in-cheek competition sketch for an extension to our own headquarters building at 66 Portland Place proposes a 'temple' structure intended to house the ���������� President as well as a members' swimming pool, bandstand for events and a radio mast to give the President direct access to the worldwide media.

Top: 1981 competition sketch for the ���������� by an unknown architect, courtesy ���������� Collections, and below: The ���������� headquarters at 66 Portland Place, designed by George Grey Wornum, as it looks today

1960 competition design for a shopping centre at the Elephant & Castle by ErnöGoldfinger

Despite this shopping centre design never being realised, Ernö Goldfinger nevertheless made his mark on Elephant & Castle with his design for the government office block Alexander Fleming House, now a residential tower known as Metro Central Heights. The selected shopping centre design by Boissevain & Osmond was the first covered shopping centre in Europe when it opened in 1965. Today the shopping centre is earmarked for demolition, the central point in a London neighbourhood undergoing huge change.

Top: 1960 Ernö Goldfinger unexecuted competition design for Elephant and Castle, courtesy ���������� Collections, and bellow: 1965 Bill Toomey photograph of Boissevain & Osmond's executed design, courtesy ���������� Collections

1956 early scheme for the Barbican Estate by Chamberlin Powell & Bon

Chamberlin Powell & Bon's design for the Barbican Estate went through several iterations. The original 1954 brief was smaller in scale than the complex eventually built, and comprised housing for 5,000 residents. Chamberlin Powell & Bon responded by proposing a ring of tall office blocks with clusters of dwellings arranged around a series of courtyards. This drawing shows the Barbican concept developing while revealing very different elevations to those executed.

Top: 1956 Chamberlin Powell & Bon early drawing for the Barbican Estate, courtesy ���������� Collections, and Below: The Barbican Estate as built, photographed in 2017, courtesy Danilo Leonardi / ���������� Collections

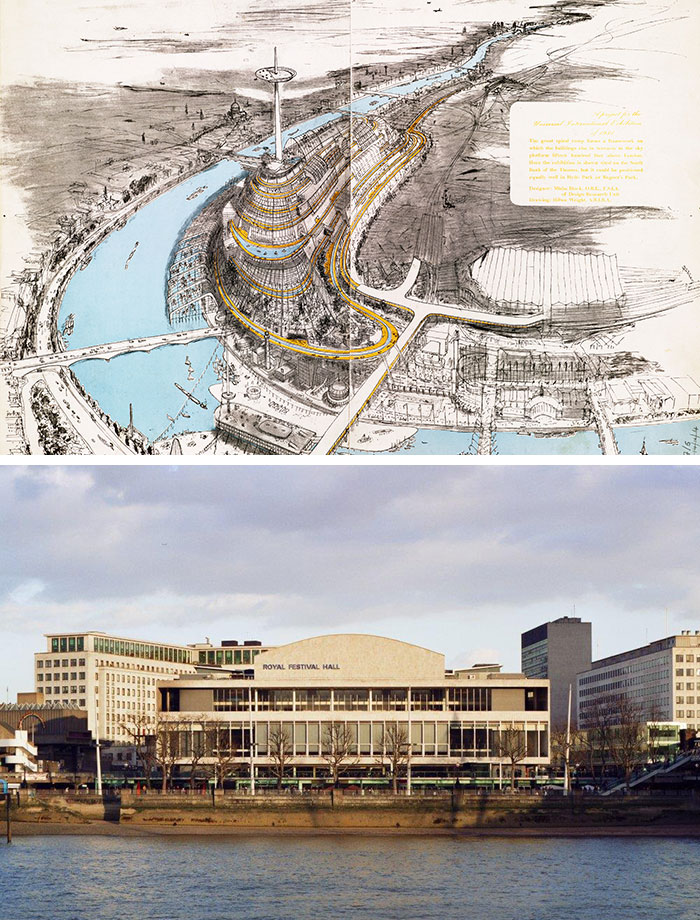

1950 unexecuted design for the Festival of Britain exhibition complex, South Bank, by Sir Misha Black

Although this design for a large riverside structure in the form of a giant glazed spiral ramp was never realised, Sir Misha Black was a key figure in the 1951 Festival of Britain complex, designing the Regatta Restaurant that neighboured the main 'Dome of Discovery' building by Ralph Tubbs. The architectural legacy of the Festival of Britain survives in the form of the London County Council Architects' Department's Royal Festival Hall.

Top: 1950 Sir Misha Black unexecuted design for the Festival of Britain, courtesy ���������� Collections, and Below: 2008 photograph of the Royal Festival Hall, courtesy Christopher Hope-Fitch / ���������� Collections

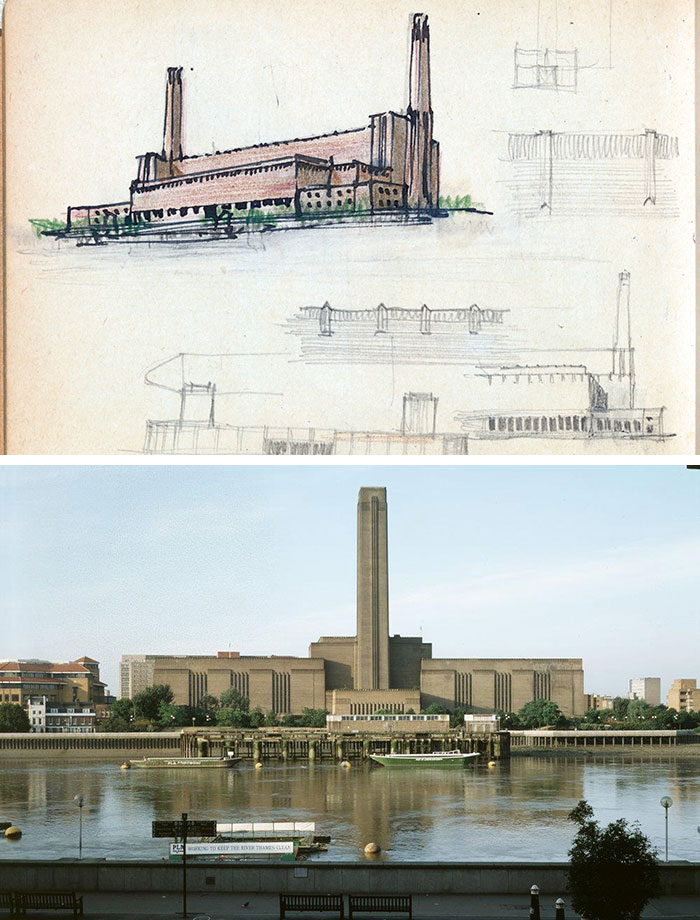

1942 Sir Giles Gilbert Scott studies for Bankside Power Station

This early study for Bankside Power Station (now Tate Modern) is subtly - but importantly - different from the final building. The drawing shows two chimneys, one of which was later scrapped in order to preserve views of St Paul's Cathedral. The remaining chimney was also reduced in height. Original plans for Bankside Power station had envisaged a coal power station, but this was later switched to oil, which could be stored in underground tanks and therefore removed the need for larger storage above ground.

Top: 1942 Sir Giles Gilbert Scott studies for Bankside Power Station, courtesy ���������� Collections, and Below: 1995 photograph of Bankside Power Station (now Tate Modern), courtesy Janet Hall/ ���������� Collections

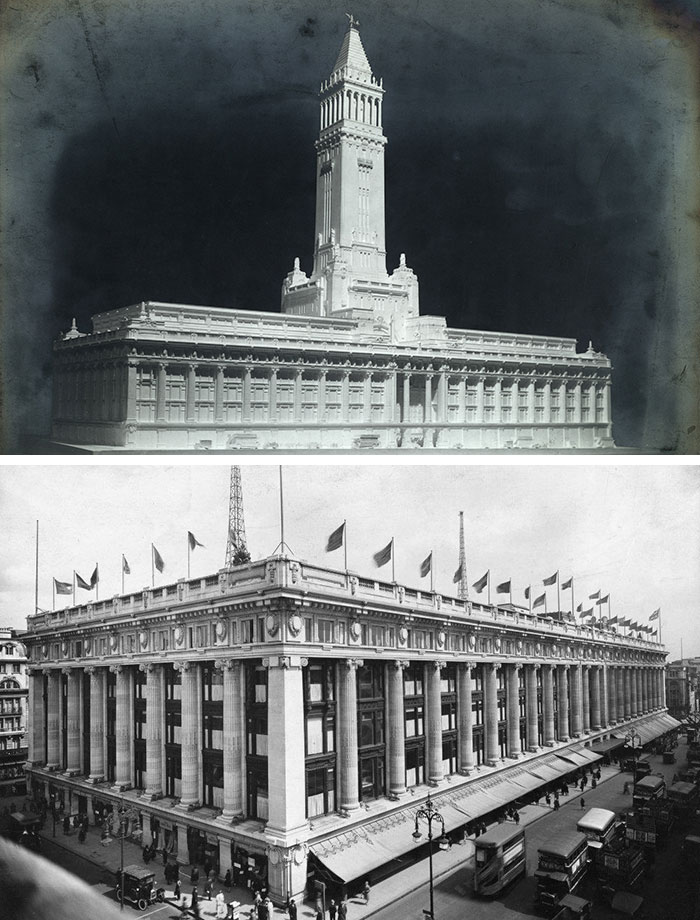

1925 photograph of a plaster model of a proposed tower to be built over Selfridges department store, by Sir John Burnet & Partners

After Selfridges department store opened in 1909, building works continued to be carried out, with the main entrance not complete until 1928. Apparently not content with a building that defied previous limitations of construction (it was one of London's earliest examples of steel cage frame construction, supporting a frontage made more of glass than stone or iron works), Harry Gordon Selfridge had ambitions - never realised - to construct an immense tower above the main building, and to excavate an underground tunnel linking the store directly with Bond Street Underground Station (to be renamed Selfridges). This model shows one of the tower proposals, still dwarfed in scale by Philip Tilden's scheme.

Top: 1925 model for a proposed tower over Selfridges by Sir John Burnet & Partners, courtesy ���������� Collections, and Below: Selfridges photographed shortly after completion (without tower) in 1929, courtesy ���������� Collections

1867 Edward Middleton Barry design for the proposed National Gallery

Remember the furore over plans for the National Gallery extension in the 1980s? It wasn't the first time designs for the National Gallery had been scuppered. This proposal by Edward Middleton Barry won an 1866 design competition for a complete rebuilding of the National Gallery, but its domed structure was denounced by critics as "a strong plagiarism on St Paul's Cathedral". Barry's contribution was scaled back to an extension to the existing building, which had been designed by William Wilkins. Perhaps adding insult to injury, Barry had been similarly passed over only a year earlier in a competition for the Royal Courts of Justice, the commission for which was awarded to George Edmund Street despite the judges having recommended Barry's design.

Top: 1867 Edward Middleton Barry proposal for the National Gallery, courtesy ���������� Collections, and Below: 2007 photograph of William Wilkins' National Gallery, courtesy Christopher Hope-Fitch / ���������� Collections

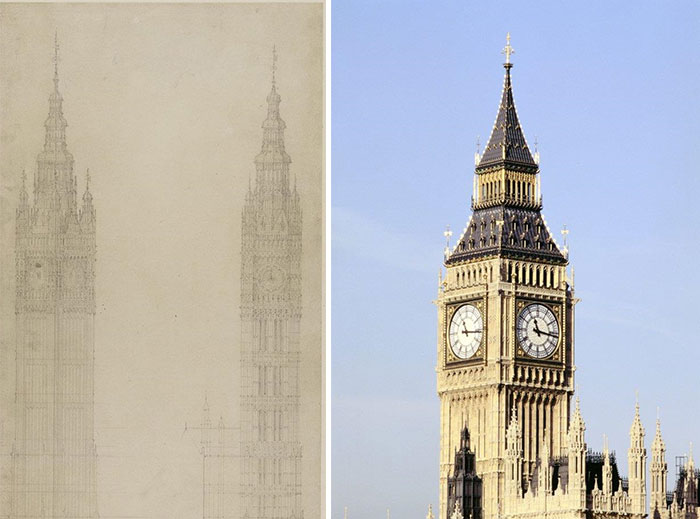

1840 Charles Barry designs for the clock tower, Houses of Parliament

London History Day is celebrated on the anniversary of when 'Big Ben' first started keeping time (31 May 1859) - so it would be remiss of us not to include an alternative proposal for London's best-known clock tower. Charles Barry’s designs for the reconstruction of the Houses of Parliament did not originally include a clock tower - he was only asked to include it later. This preliminary study, while ' Gothic Revival' in style, has the addition of a surmounting turret in a 'Moorish' style. The final tower design was eventually built in 1859, being renamed Elizabeth Tower in 2012 but more commonly referred to as Big Ben after the largest of its five bells.

Left: 1840 Charles Barry designs for the clock tower, Houses of Parliament, courtesy ���������� Collections, and right: 'Big Ben' photographed in 1994, courtesy Joe Low/ ���������� Collections

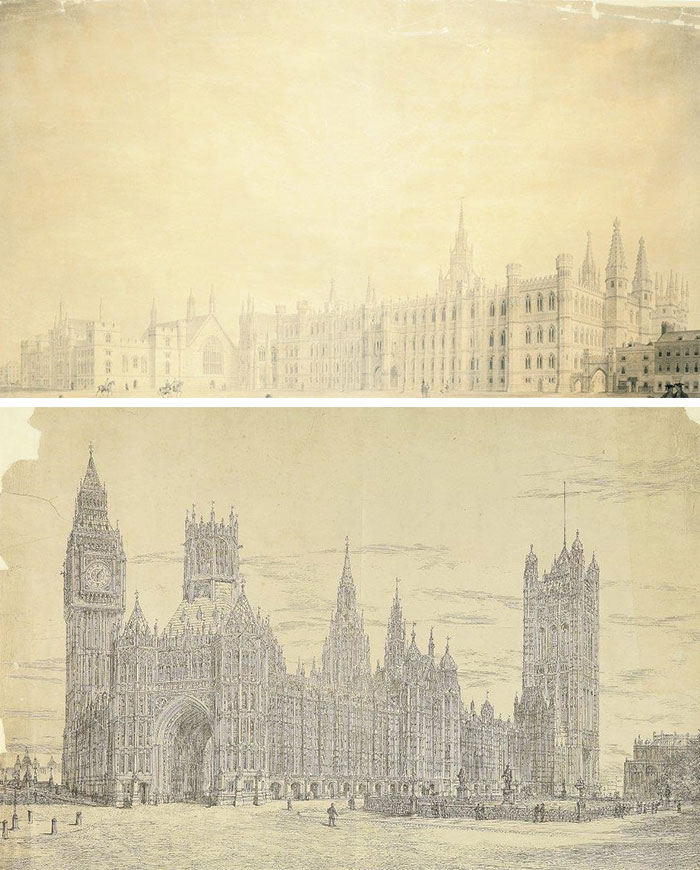

1830 Lewis Nockalls Cottingham competition design for the New Houses of Parliament

Following the Great Fire of 1834 a competition was set up to design the new Houses of Parliament, and in just four months, 1,400 drawings by 97 entrants had been submitted. The designs ranged from a vast neoclassical ‘Senate House’ in St James’ Park by Joseph Gandy, to this Gothic Revival design by Lewis Nockalls Cottingham. The Gothic style was actually specified by the judges, as the classical architectural style was associated with the French Revolution and Republicanism. Ironically, the winning neo-Gothic design by Charles Barry was heavily criticised by his colleague Augustus Pugin as ‘All Grecian, sir; Tudor details on a classic body.’

Top: 1830 Lewis Nockalls Cottingham design for the Houses of Parliament, courtesy ���������� Collections, and Below: 1860 print of Charles Barry's winning design, courtesy ���������� Collections

Discover more unrealised schemes in our special collection of images on ����������pix, ����������'s image library.