Papered Spaces: Clerical Practices, Materialities and Spatial Cultures of Provincial Governance in Bengal, Colonial India, 1820s-1860s

Dr Tania Sengupta, University College London

Awards 2019 ���������� President's Awards for Research

Category History & Theory

This research was the 2019 Research Medal winner and the winner for the 'History & Theory' category in the 2019 ���������� President's Awards for Research.

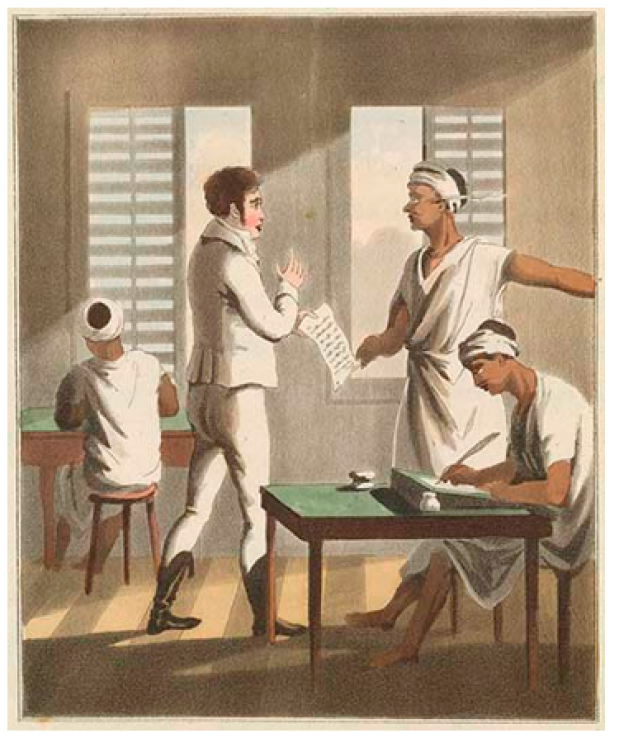

British colonial governance in India was based on global technologies of writing produced by European mercantile colonialism and equally fundamentally, as analysed by Christopher Bayly, on the extraction of Mughal administrative knowledge embodied within a Persianette Indian clerical class, its materialisation into official forms such as paper documents, and further, on what Bhavani Raman has called a scribal-clerical ‘habitus’. A paper-centred culture of bureaucratic practices was also the hallmark of the early-nineteenth century colonial government in Bengal that Jon Wilson calls one of the earliest modern states in the world.

This research focuses on the architecture, spaces and material culture associated with colonial paper-bureaucracy in Bengal. It argues that the paper-based and writing-oriented habitus of colonial administration also mandated a chain of related materialities and spatialities – from paper records to specific types of furniture, spaces and architectures of colonial governance. Focusing on the colonial cutcherry [office] complex that formed the nerve-centre of zilla sadar [provincial administrative] towns of Bengal, I look here at the roles, spatial relationships and design developments of such ‘papered spaces’ as record rooms and clerical offices. The work demonstrates how paper became a key agent of colonial governance, not merely in itself, but also through the expanding spheres of its logic, which permeated in a profound manner the material-spatial culture and ‘lifeworld’ of the cutcherry. I also reflect on how paper-practices of colonial governance had to necessarily work in conjunction with other more immaterial and mobile circuits of colonial knowledge and information spread over the town and country, as also how such paper-governance was fed, for example, by paper and printing industries.

For the research, I combined extensive on-ground documentations of the material fabric of the buildings with archival research in India and the UK looking at governmental papers, period literature and art.